These are people who are much more fickle and demanding than your average assembly line designer or Amazon warehouse manager, and even they often don’t know what their central objections really are. If we want robots to invade the home in a form more powerful than the Roomba, we’ll need to figure out what ineffable human qualities robots lack — and add them. A team from Japan’s Kansai University has started showing just a selection of their work on this topic; whether it’s filling the role of an elder-care helper or a prostitute, this team knows that if robots don’t feel human, humans will never start feeling robots.

The sex-bot industry has really been at the forefront of the push to make robots feel human; though they’ll always be somewhat creepy, there’s something almost touching about the seeming need to invest a masturbatory device with humanity and even emotion. Still, by their nature sex-bots will try to mimic realistic human attributes, from blinking to breathing to movement. Most robots, though, don’t interact with humans so intimately, and as such will benefit from more abstract nods to humanity; like GERTY from the movie Moon, even a simple smiley-face can add enormously to the feeling of interacting with a real intelligence.

|

| Though it had just a little smiley face and some audio morphing, Moon’s GERDY was loveable and memorable. |

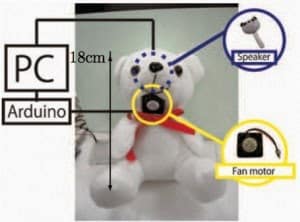

But we can go further. What if a robot shivered and even got goosebumps in response to a cold breeze or a scary anecdote? What if you could feel its breath when it spoke, and more violently as the volume increases? What if it would bead with sweat due to heat, or even (fake) emotional stress?

The idea behind these inventions is that we humans are more inclined to trust signals that are communicated involuntarily. So if a robot was to enter your bedroom in the middle of the night and say, “Unknown human detected on the lower floor,” you’d be much more likely to take it seriously if that statement came accompanied by a worried face, heightened breath, and a trembling hand. The emotional timbre of the voice will also be incredibly important; somewhere, someone is writing an algorithm to auto-tune any statement from casual to urgent.

|

| Simple, no-frills emotional feedback will probably not be most effective until we can span the Uncanny Valley. |

Of course, this does seem a bit like putting the cart before the robotic horse; there hasn’t even been a telepresence robot yet adopted on a large scale, and that has the benefit of having a real human for a face. If our home robots sweat, will they refill their own sweat reservoirs, or will we be running plumbing to our robot charging stations? Will we be able to switch their emotional features off in return for increased battery life? Will robots be equally human to all comers, or present strangers with a colder shoulder than to their owners?

I have to wonder whether these sorts of efforts, which will never truly replace a real human emotional trait, might be better suited to roles where human interaction is already pretty superficial. A robotic Walmart greeter might manage the same level of humanity as a real one, and even in taking your order a robot waiter could do some minor human-style interacting. Think about how mechanistic most of your interactions with service people already are, anyway; think a robot couldn’t be programmed to ask about your day? It could probably even be better at pretending to care. And in the context of telepresence robots, we can imagine a bunch of executives stepping into biomonitoring rigs so their full boardroom presence can be simulated as accurately as possible.

|

| This robot adjusts its breathing strength with vocal volume. |

Still, a real feeling of humanity in a robot is probably going to have more to do with the robots handling of input than on its output. Robots need to be able to correctly pick up on our subtle emotional cues. If one can notice that I’m tired and grumpy when I get home from work (maybe probing my body language, heart rate, and core temperature with various cameras) I ultimately don’t care how realistic it seems when it brings me a beer and a foot-pillow. It’s the bringing or not-bringing that matters the most. A dog doesn’t emote in a particularly human way, but we can grow to understand and appreciate the meaning behind its alien emotes. We could just as easily grow accustomed to a new sort of robot body language too, given how superficial our relationships with those robots will be — at least at first.

Source : ExtremeTech